Originally Printed in the NY Times

Originally Printed in the NY Times

The rolling fields of Max Yasgur's old farm are once again swathed in a psychedelic quilt of tie-dye-clad music fans. This time, though, the fans are carrying cellular telephones, and the automatic teller machines are just a few steps away.

''I think high-tech is kind of infringing on the hippies,'' said Kevin Carter, who was working at a one-hour photo development stand, one of the many commercial vendors at a three-day concert called ''A Day in the Garden,'' on the site of the original Woodstock festival. ''Some of the die-hard Woodies are having problems with it.''

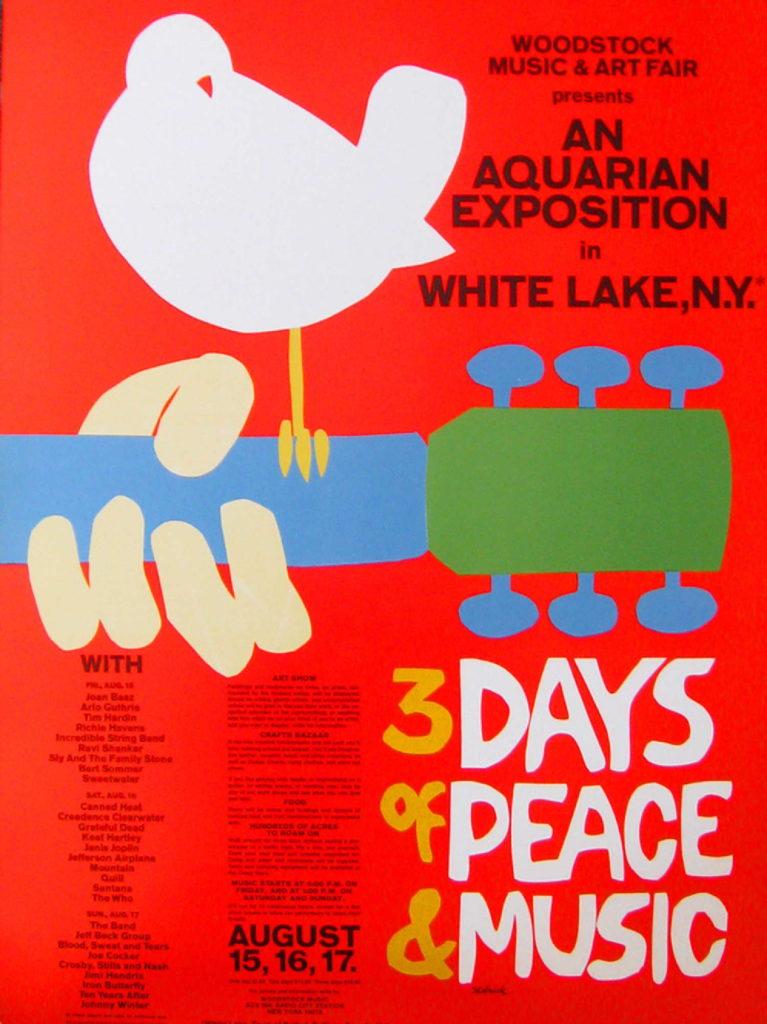

It was 29 years ago this weekend that hundreds of thousands of flower children flocked here for a three-day festival of peace, free love and music that defined the era and turned these hayfields into a pilgrimage site for generations of Americans.

It was 29 years ago this weekend that hundreds of thousands of flower children flocked here for a three-day festival of peace, free love and music that defined the era and turned these hayfields into a pilgrimage site for generations of Americans.

In 1969, they drove, walked or danced into the fields, guided only by the spirit of the moment. Today, a clicking, fluorescent highway sign beckoned concertgoers off Route 17. From there, the New York State Police directed traffic. The edge of the concert area was marked by a line of ticket booths, where the Gerry Foundation, which now owns the Yasgur fields and organized this weekend's event, charged $35 per person per day. (Admission was free for children under 12.)

Event organizers said that 12,000 tickets had been sold for Friday and that 4,000 to 6,000 children had come in free. They estimated that 22,000 people attended today's performances, including about 6,000 children. State troopers estimated a slightly smaller crowd today, about 18,000 to 20,000. As it is currently set up, the Woodstock site can accommodate 30,000 fans.

The performers today included some brand-name 1960's stars like Richie Havens, Lou Reed, Joni Mitchell and Pete Townshend of the Who. Organizers, however, said they expected the largest attendance on Sunday when 90's bands, including Goo Goo Dolls and Third Eye Blind, are scheduled to play.

This weekend's event was so carefully orchestrated -- with prearranged traffic patterns, dedicated parking, security and medical personnel -- and the crowd, including many parents with young children, was so mellow, that this hardly seemed the same place immortalized by marijuana-smoking hippies dancing naked in the mud.

To get down the hill to where the musicians were performing on a state-of-the-art stage (the same one Garth Brooks used last summer in Central Park), concertgoers had to pass by a wide area of vendor tents.

For $20, Cornelius Alexy was selling peace sign necklaces fashioned from pieces of the ''original'' chain-link fence that surrounded the Yasgur property in 1969 -- complete with a certificate of authenticity. Across the way, pastrami sandwiches could be bought for $7 each. Beer cost $3. For the more health conscious, there was a fruit and juice bar.

More than a mile away, at Max Yasgur's old farmhouse, hundreds of stalwart defenders of Woodstock Nation gathered to protest the commercialism. They said the corporate takeover of Yasgur's farm had robbed them of their annual pilgrimage to the '69 concert site.

More than a mile away, at Max Yasgur's old farmhouse, hundreds of stalwart defenders of Woodstock Nation gathered to protest the commercialism. They said the corporate takeover of Yasgur's farm had robbed them of their annual pilgrimage to the '69 concert site.

''These are the people who were at the original Woodstock,'' said Rebecca Swan, 55, who drove from Texas to the original concert and now travels the country living in an old yellow school bus. ''These are the people who wish they were at the original Woodstock or people who love the idea of the original Woodstock. These are people who are being prevented from making their pilgrimage and expressing their beliefs by rich people and the government.''

Ms. Swan acknowledged the irony in the battle that is currently brewing between the Gerry Foundation, which owns the original concert site, and another group, Woodstock Ventures, which owns the name and the rights to the original Woodstock event. At the same time, some of the fans who attended the '69 concert have a lawyer pressing their case for free access to the site.

Such controversy, however, did not intrude on the concertgoers who were enjoying the modern-day amenities. As the folk singer Melanie began to play this morning, there were already lines at a bank of Bell Atlantic public telephones and at the portable A.T.M.'s that were trucked in by Fleet Bank.

Concert organizers said they tried to modernize without undermining the event's hippie soul. ''We developed 10,000 parking spaces,'' said Michael J. DiTullo, a vice president of the Gerry Foundation. ''Not with blacktop, of course, with green, with grass.'' He said the foundation has big dreams for Bethel, including possibly developing rock-and-roll resort hotels. ''This will be the venue of the next millennium,'' he said.

Most importantly, the fans said, they came for the music. ''We came in on Thursday and set up the tent, and Don Henley was tuning up,'' said Mike McGrath, 43, of Newburgh, N.Y. ''It was great.''

Gwynne Watkins, an 18-year-old Joni Mitchell fan from Richmond, N.J., said she came to recapture the essence of a bygone era. ''There aren't enough concerts like this,'' she said.

''Everything is always enclosed, where you can't meet anybody and you can't see anybody.''